Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

Shopping Cart

Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

I first heard about 3D scanning applied to fine art reproduction about ten years ago. A university in the Netherlands collaborated with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam to create 3-dimensional scans of van Gogh’s original paintings. The process was time-intensive and laborious, and involved stitching together thousands of individual photographs taken under strict lighting conditions.

So, I wasn’t totally unprepared when the German scanning company I was working with told me they could make 3D scans of my artwork.

I had been searching for a scanner that could photograph wet oil paintings to create high-resolution images of my work without waiting eight weeks for the painting to dry. I couldn’t use a traditional scanner, which required the artwork to be placed face-down--I needed the scanner to light the paintings from above, creating little shadows from the texture of the brushstrokes and giving the illusion of texture to my prints.

My Cruse scanner was the perfect solution to creating beautiful, 2-dimensional reproductions of my paintings with the illusion of texture. But I was about to discover the magic of 3-D scanning and creating real texture in my reproductions that you could actually touch.

German technicians install Erin’s new Cruse scanner. This 2nd-generation scanner is bigger than Erin’s first scanner, weighs 13,000 lbs, and allows her to scan colossal-sized artwork.

Before my Cruse scanner, I created digital images of my work with flash photography, bouncing the light off huge reflecting walls. The setup was touchy and hard to get exactly right, and it was difficult to get an entire large painting in focus.

Earlier than this, I was photographing my artwork outside. After years of trial and error, I had developed this system of photographing my work: first, I would wait for a sunny day with the sun low on the horizon (early morning was best, since the light was clearer in the morning). Next, I would have someone hold up a 6-foot-wide metal frame with a thin mesh stretched inside. This was called an “f-stop screen,” a photographer’s trick for decreasing the amount of light coming through to the subject. I turned the painting so that the sunlight came from the side and cast little shadows across the artwork. Finally, I used a professional Canon SLR camera fitted with a circular polarizing lens, which cut out any reflective glare caused by the sunlight.

Using a camera worked well to get relatively high-resolution images—any of my paintings you see online that were created before 2019 were captured using these photography techniques.

You can see the higher resolution captured by the Cruse scanner compared to my old Canon camera.

When I first started painting in my Open Impressionism technique back in 2008, I only had a small point-and-shoot camera and no lighting control. It is too bad that most of my early works were photographed so poorly that I can’t share them online or print them in books. These early classics will never be made available for prints since the images are out of focus, too low-res, or have too much glare.

Of course, I never imagined I would need to archive my works for future generations, but now every time we get a classic painting back to varnish or re-frame, we jump at the chance to properly scan it in full 3D magnificence.

With over 3,000 paintings completed and a growing recognition of my Open Impressionism style, it is crucial to have a proper catalogue raisonné, which comes from the French phrase “explained catalog” and is used to establish the value of an artist’s work at auction. A catalogue raisonné is a list of every single piece of artwork created by an artist, including dimensions, descriptions, owner and exhibition history, copies and forgeries, duplicate painting names, etc. (Did you know when I was first painting, I didn’t bother to name all my paintings? I didn’t have the robust system I have in place now to ensure that I never use the same painting name more than once. So, many of my classic early works are either unnamed or have the same name as a more recent painting.)

I am glad to have finally discovered a refined way of preserving and archiving my artwork, in more dimensions and detail than any artist before me. Honestly, I think I could teach that university in Amsterdam a thing or two about how to really capture the essence of an original Van Gogh.

With 3D printing technology, I can also recreate prints with the exact brushstroke texture of the original oil painting. My “3D Textured Replicas” are beautifully vibrant and richly textured, almost indistinguishable from the original from a few feet away.

Texture is such a big part of how I see the world, how I interpret landscapes, and how I communicate color. Texture is the rhythm of my work.

As the first artist to use a Cruse scanner and pioneer textured replicas, I hope to pave the way for future artists to preserve their work in all three dimensions and set a new standard for archiving paintings.

You can find all paintings that have been scanned using the Cruse Scanner by selecting the category “3D Textured Replicas” on my portfolio page here on the website. Here are just a few classics that are currently available as textured replicas.

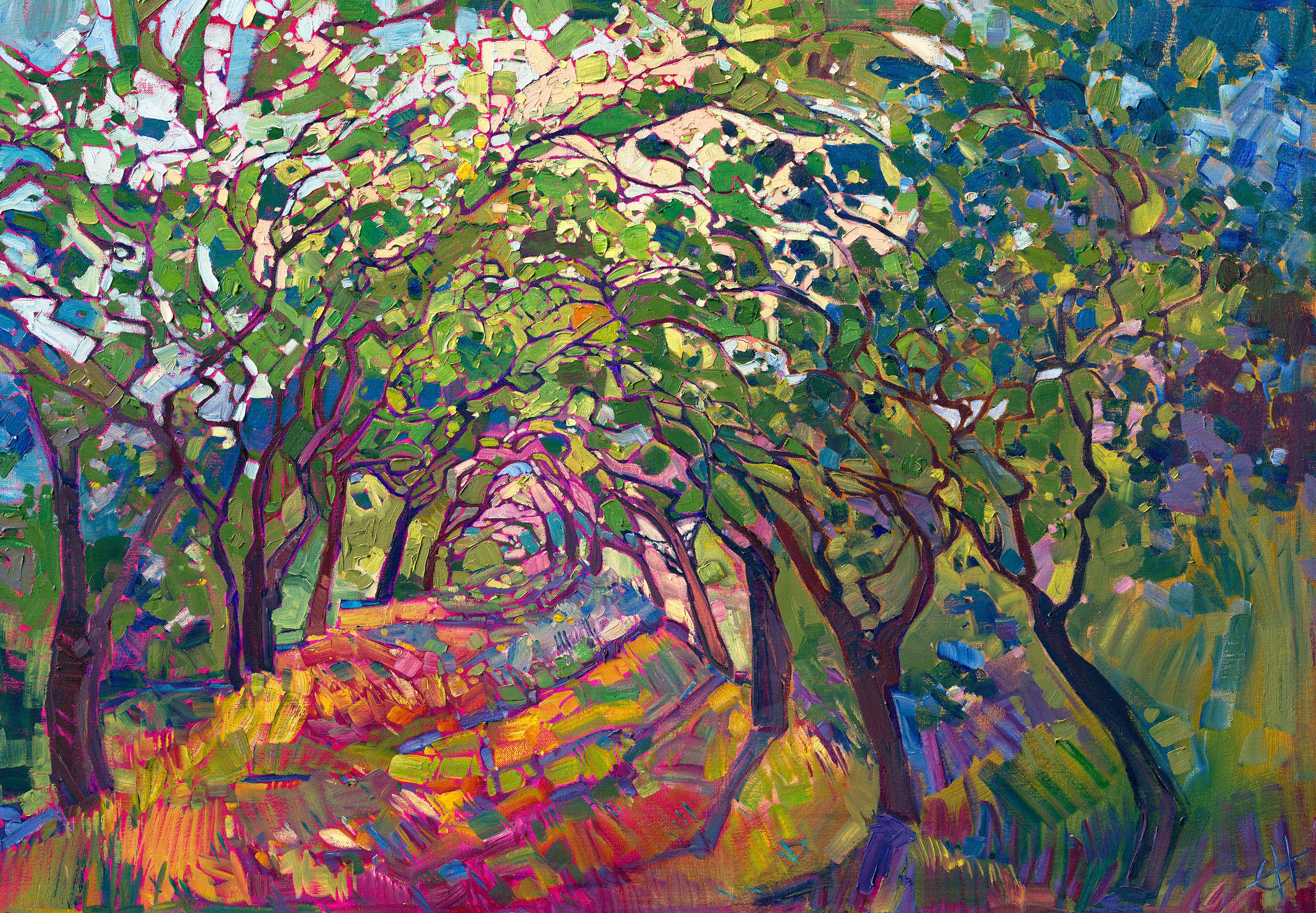

The Path is one of Erin’s iconic classic paintings that will forever be preserved in three dimensions.

Cypress Water is a classic water painting that captures the movement and colorful reflections of Lone Cypress in Pebble Beach, California.

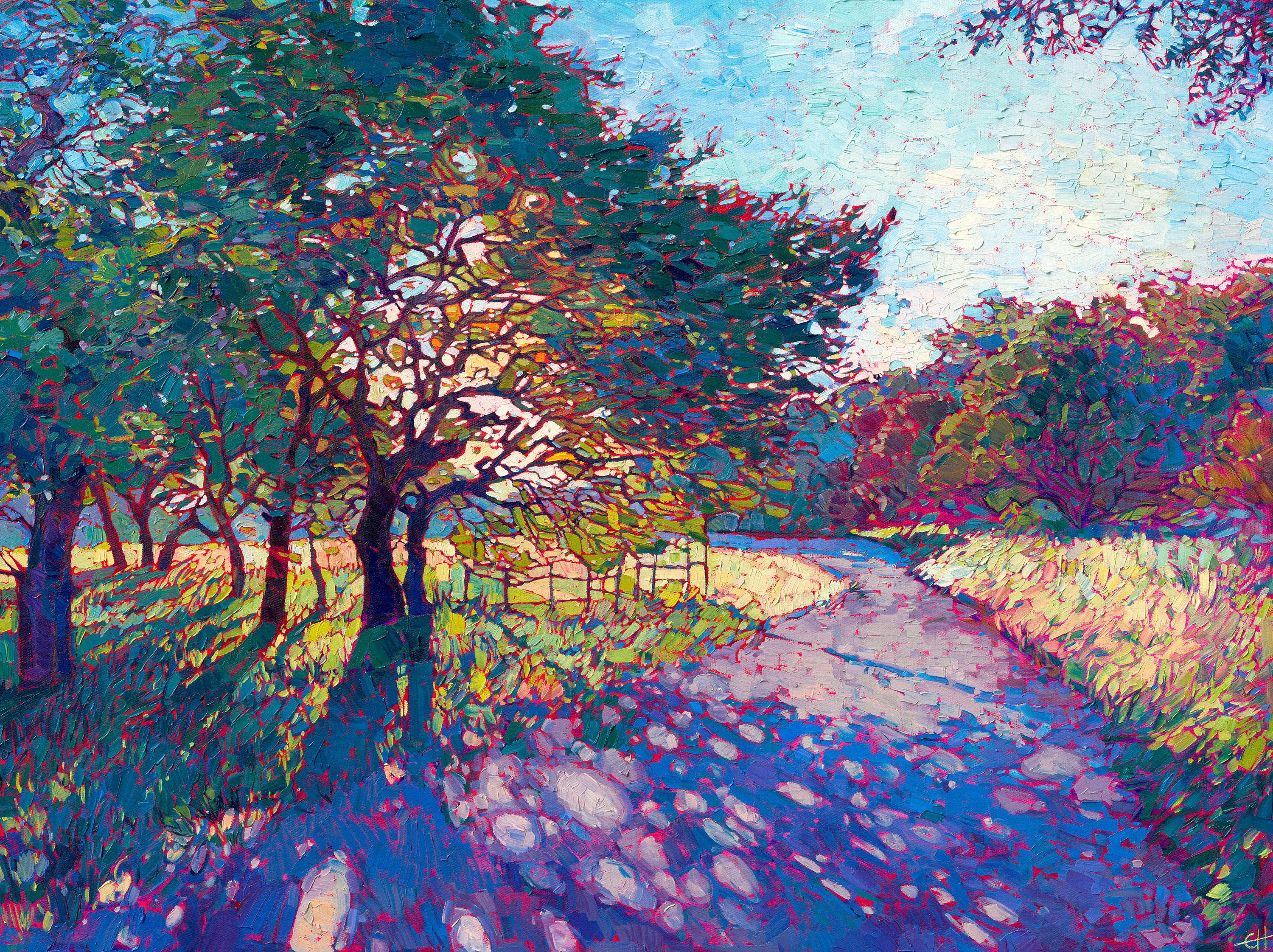

Crystal Path, part of the Crystal Light Collection, has been preserved in three dimensions, allowing viewers to enjoy the play of light and shadow featured in this piece and in that quintessential collection.

These classic works are forever preserved in perfect three dimensions and are available as limited edition 3D Textured Replicas. Explore more by clicking here.

Discover the artist at the forefront of modern impressionism.

About Erin

ERIN HANSON has been painting in oils since she was 8 years old. As a teenager, she apprenticed at a mural studio where she worked on 40-foot-long paintings while selling art commissions on the side. After being told it was too hard to make a living as an artist, she got her degree in Bioengineering from UC Berkeley. Afterward, Erin became a rock climber at Red Rock Canyon, Nevada. Inspired by the colorful scenery she was climbing, she decided to return to her love of painting and create one new painting every week.

She has stuck to that decision, becoming one of the most prolific artists in history, with over 3,000 oil paintings sold to eager collectors. Erin Hanson’s style is known as "Open Impressionism" and is taught in art schools worldwide. With millions of followers, Hanson has become an iconic, driving force in the rebirth of impressionism, inspiring thousands of other artists to pick up the brush.