Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

Shopping Cart

Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

I first encountered Erin Hanson’s art in New York City. Ken Ratner, a talented artist, curator, and writer, had invited me to his Manhattan apartment to look at his burgeoning art collection. It was a cozy apartment filled with art befitting a collector of modest means but large ambitions. As I worked my way through dozens of works of art, I noticed two things. First, Ratner had an unerring eye for quality. Second, his collection featured the most quintessential of American subjects, the land. Many of America’s finest artists, from Thomas Cole to Albert Bierstadt to Edgar Alwin Payne, had elevated the land to the highest art form. If the land was prominent within Ratner’s collection, then Erin Hanson was the star in the Western sky. I was immediately struck by her talent.

Hanson is among those rarest of artists, she has created her own signature style, which she calls Open Impressionism. This allows her art to stand out in a crowd and uniquely positions her to continue in the impressionist tradition. Second, like all great artists painting in the Realist tradition, Hanson is a storyteller. She uses narrative intuitively to tell universal stories. Third, Hanson uses color and texture, key components of her Open Impressionism style, to embody the land. In the following pages, I will expand on these points by looking at some of her paintings in detail. Ultimately, the goal of this analysis is to help viewers understand what makes Erin Hanson’s art so special and enduring.

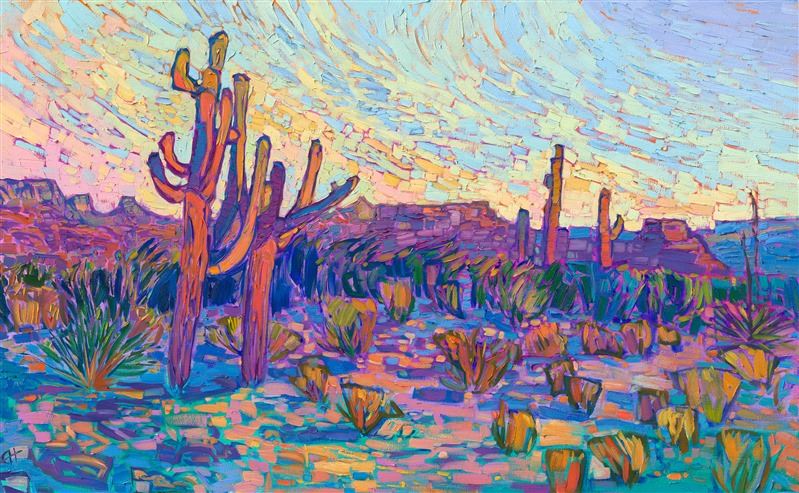

"Saguaro Hues" by Erin Hanson

To understand Erin Hanson’s art is to understand Open Impressionism, a style the artist pioneered, and which is being taught in art schools and colleges around the world today. Open Impressionism blends impressionism, expressionism, and the plein air style first made famous by Monet. Hanson uses minimal brush strokes and applies paint in the thick, impasto style favored by modern art styles. Historically, oil painters have built up a painting, layer by layer, to achieve three-dimensional illusionism. Instead of layering, Hanson lays her bold paint strokes side by side without overlapping. You get the sense, looking at her dynamic canvases, that she works hard to get each stroke right the first time. Such strong, thick, clean brush strokes tend to give a mosaic or stained-glass appearance to her paintings – strong, solid, eternal. Yet the solid paint strokes also convey a sense of movement and spontaneity. Hanson uses a limited palette of only five pigments; the resulting vivid, highly saturated colors let the viewer’s imagination run wild.

Although Open Impressionism is a new, unique style, it continues the work of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Monet and Van Gogh come immediately to mind. Like the Impressionists, the purpose of each painting is to capture the fleeting and momentary light seen out of doors, especially during early dawn and sunset. Like other Impressionist painters, Hanson’s work appears more abstract when viewed up close and "goes into focus" when seen from a few feet away. Her devotion to innovation paired with her remarkable work ethic are indications that her art will long be remembered.

"Dance of Irises" by Erin Hanson

Hanson’s broken brushwork and pure, bright colors are fresh and spontaneous. It is as if we are standing over the artist’s shoulder, watching her rough out shapes, masses, and shadows. You can smell the linseed oil drying, feel the earth beneath your feet, and breathe in the sweet floral scents floating in the Western sky. This is immensely satisfying to us, the viewers because it allows us to vicariously experience some small part of the magic of art, the alchemy that allows oil and pigment on canvas to become beauty personified. While it is easy to be dazzled by Hanson’s technical skill, her paintings are more than just symphonies of color, light, and texture.

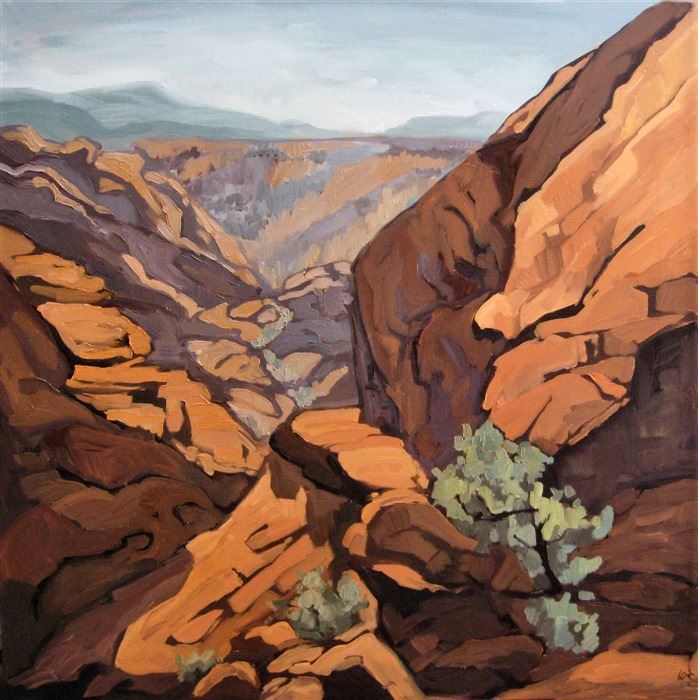

Hanson is a master storyteller because each painting connects the past and the present into coherent and deeply satisfying narratives. For example, in an early painting like Sweet Pain (2008), Hanson connects her experiences as an avid hiker and climber with the immediacy of her painting technique. Here, the artist offers a view of a difficult place to access, a climbing wall in Red Rock Canyon, that she had spent many afternoons struggling against. In accessing this difficult, remote place, the artist offers the viewer a beautiful vista after a triumphal climb. We are rewarded, in much the same way the artist was all those years ago, with a path through the rugged landscape and access to the beauty of nature. We know, intuitively, that this painting, though immediate in one sense, is also a pivotal scene in a story and a timeless homage to the adventurous spirit in all of us.

"Sweet Pain" by Erin Hanson

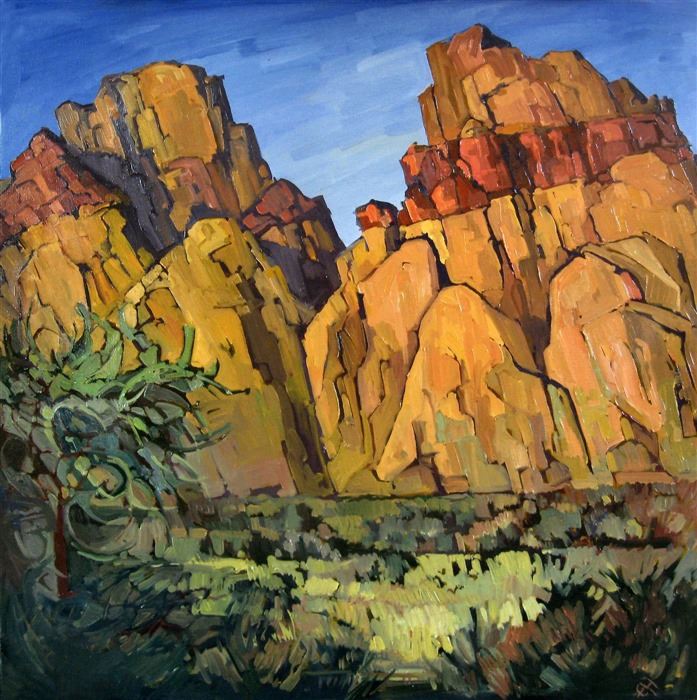

While Sweet Pain offers us a visually satisfying, if circuitous, route through the landscape, Rainbow Mountains II stops us dead in our tracks. Rather than a picturesque scene, Rainbow Mountains II offers a sublime contemplation of nature and the limits of human experience. This is a place most of us will never reach. The brilliant blue sky above the twin peaks of the mountains recedes into the distance, indicating that there is more to see. Yet, our eyes are frustrated, unable to find a way forward. We know, intuitively, that we’ve arrived at the base of the mountain after a long hike, dropped into the narrative at a moment of contemplation just after the hike ends and just before the challenging climb begins. We are reassured to know that these spots exist and that this adventurous artist went out and collected these rare scenes for our viewing pleasure. Much like a painting of a volcano in Hawaii or a snowstorm in Montana, Hanson’s paintings are successful, in part, because we know they represent real events and places. They record an experience as much as they do colors, forms, and shapes. In viewing her paintings, we imaginatively recreate these experiences in our mind’s eye. In this small way, then, we are part of the story, part of the magic and grace and beauty of nature and art.

"Rainbow Mountains II" by Erin Hanson

Erin Hanson is a talented artist who could easily paint any subject she wanted to – portraits, still life scenes, anything really. When I asked Erin why she paints landscapes, her answer was revealing:

"The land is the most beautiful thing I can think of to paint. All my fondest experiences growing up took place outside, camping and hiking, backpacking, and exploring the backcountry. Since I grew up in Los Angeles, getting out into nature felt so expansive and magical. I remember seeing the Milky Way for the first time – my dad woke me up in the middle of the night, while we were camping out in our sleeping bags, without even a tent, and I saw the Milky Way far away from the city lights. I remember the first time I was alone hiking through an aspen grove out in southern Utah, completely surrounded by the softly rustling leaves. I remember waking up before dawn and scrambling up a mile of sandstone rocks so I could watch the sunrise behind the famous arch at Arches National Park. Once I backpacked 50 miles across Zion National Park, and it was one of the most exhilarating weeks of my life, waking up every morning surrounded by natural beauty. When I paint, I try to re-capture these experiences."

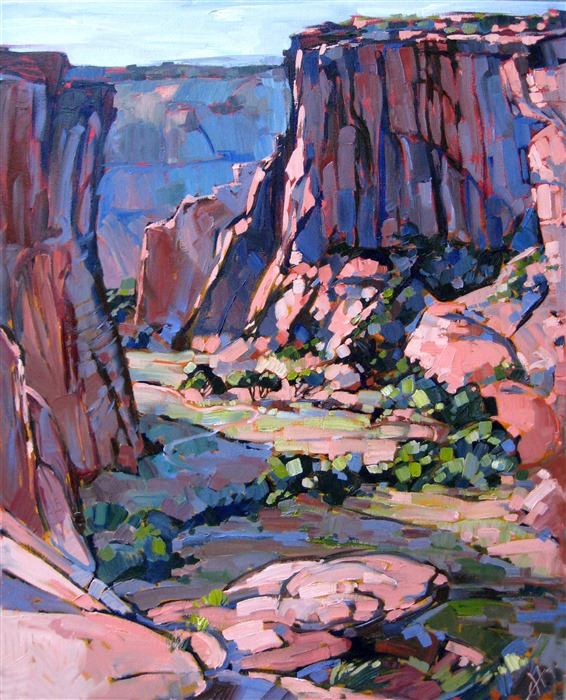

For Hanson, the experience isn’t secondary to the art – it is the reason for the art. This comes through time and time again. In Canyon Shadows (2010), we are offered a view of the timeless Canyon de Chelly. We see cottonwoods blushing green from summer monsoons. We see the shadows etched into the cliffs. We see a path cut into the mountains and through to the unknown. We see all of this because of Hanson’s adventurous spirit and attention to storytelling. As with her other paintings of the rugged West, the viewer is granted a place in the story, if only metaphorically.

"Canyon Shadows" by Erin Hanson

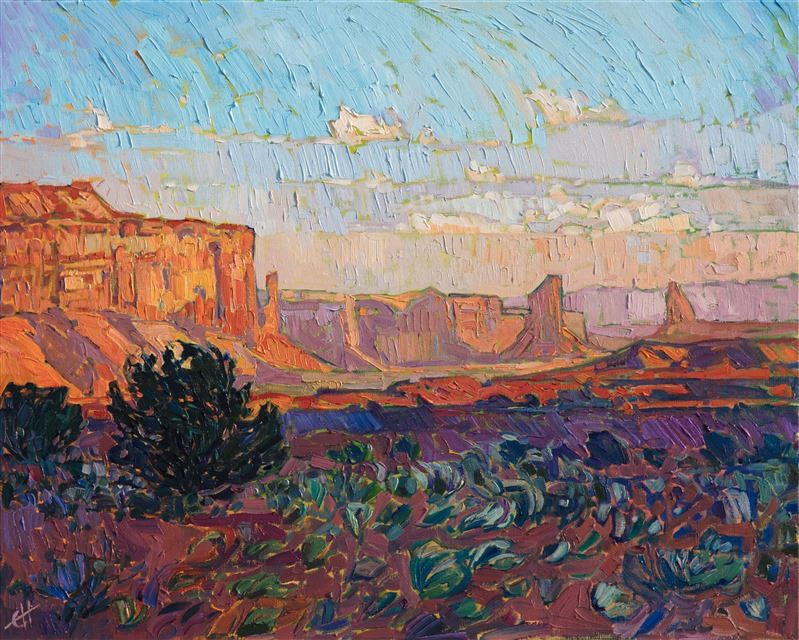

In a painting like Monument Dawn (2018), we notice the subtle pull-push between the shaded greens of the vegetation in the foreground, the warmer tones of the mountains in the middle distance, and the cool blue of the sky. This leads our eyes deeper into and through the painting, like magic, toward the iconic Monument Valley. This is the first element of what I call the Embodied Land, an effect brought about through colors that move and churn and palpably fluctuate. These colors lend vibrancy and movement to the composition, while also subtly undermining the illusionism of the painting. Colors, in short, that do their job to tell the story of the painting, while also reminding the viewer that the paint is just that - paint on canvas, a physical thing. The Embodied Land depends on the tension between the magic of illusionism and physicality of paint. In this way, the Embodied Land is the result of Hanson’s Open Impressionism style. Yet by focusing on the effect of the thickly applied paint we can see how her style lends a sense that the land is not only the subject of the painting but that it has a real, almost metaphysical presence, the almost subliminal subject of the picture.

"Monument Dawn" by Erin Hanson

Hanson frequently contrasts warm and cool colors to provide a sense of movement within her paintings. However, she also uses composition to help move our eyes through the landscape. A well-composed scene offers a sense of permanence. Composition is the backbone of any painted scene, realistic, abstract, or otherwise. Compositionally, Monument Dawn uses an implied line, from left to right, to lead our eye from the foreground to the background. This line starts at a scrub brush on the left and ends in a short, upturned rock formation, subtly linking the parts of the painting, front to back and side to side. Color and composition are used, masterfully, to provide the viewer with a partial path through the landscape and to connect the various parts of the scene. Yet, the thick, physical nature of the paint on the canvas makes the viewer question that permanence. As a result of Hanson’s Open Impressionism style, we come to the second part of the Embodied Land – the pleasant tension or contrast we feel as viewers between a well-designed and composed landscape meant to enhance illusionism, and the fluid, tactile, lived reality of the thickly applied paint itself.

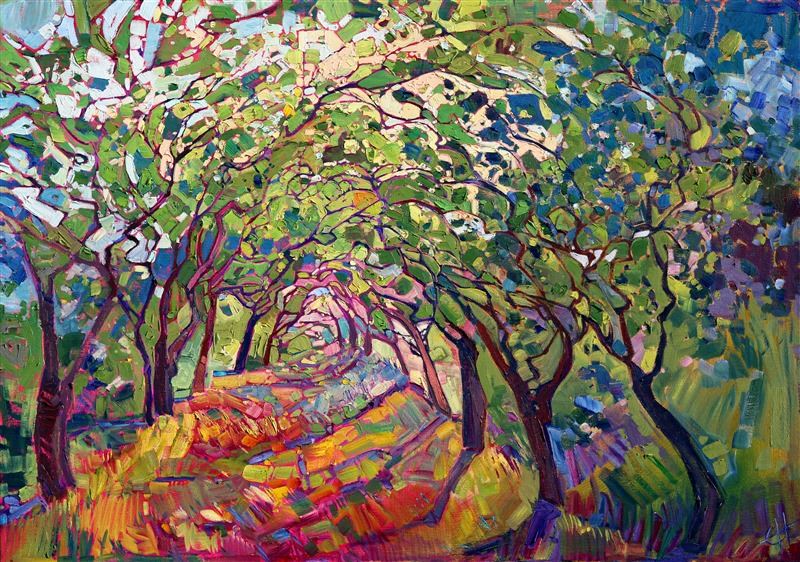

"Crystal Light" by Erin Hanson

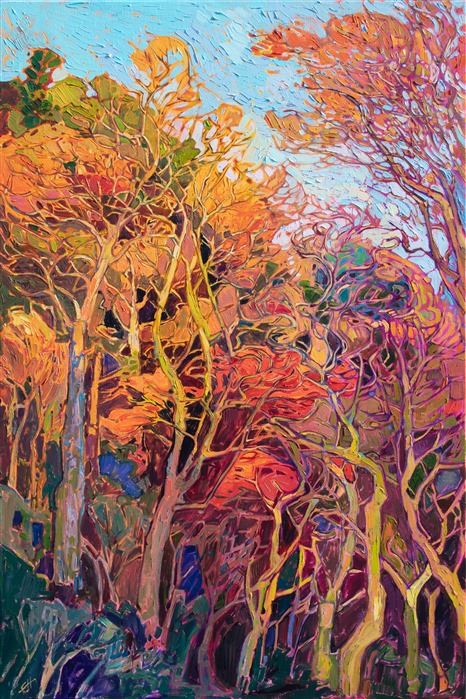

So, while color and composition lend a solid permanence to Hanson’s art, it is the tactile quality central to all her work and key to the Open Impressionism style, that brings the Embodied Land to the forefront. Applying paint thick to the canvas is a deliberate choice by the artists that have implications beyond the immediate scene being articulated. She described her technique of painting rocks to me as “delineated outlines” filled with “flat planes of saturated color.” This could well describe the basic building blocks of many of her paintings. In Crystal Light (2013), the setting sun creates vivid colors on springtime grass in Paso Robles, California. Yet they are flat planes of color, like stained glass tesserae fitted into the delicate, delineated outlines of a Gothic church window. In Hanson’s paintings then, we have an artist working in the Realist tradition who, nevertheless, pushes abstraction close to the limits. The resulting dynamic tension, between the illusionism of the scene, set up through the line, color, and composition, and the almost clay-like structure of paint applied fast and directly to the canvas, making the land seem alive, embodied, and eternal all at once. Nowhere can the embodied land be seen more clearly than in Forest Light (2019), a scene inspired by a trip the artist took to Kyoto. Here, the glorious fall-colored trees cascading down a steep hillside in Arashiyama Park seem like age-old sentinels. It is as if the landscape itself is alive.

"Forest Light" by Erin Hanson

If you are a fan of Erin Hanson’s work, odds are you appreciate Impressionism. Indeed, Hanson’s deft use of loaded brushes to place slabs of thick, impasto oil paints one next to another pays homage to the first modern art movements, Impressionism and Post Impressionism. The influence and echoes of Impressionism - the French Impressionists, like Monet and Pizzaro, as well as more recent practitioners of the style like the American artist Edgar Alwin Payne - are inescapable, felt everywhere in Hanson’s work.

Impressionism first emerged in Paris in the 1870s. Monet and his followers were modern revolutionaries in many ways. They took as their subjects the everyday happenings of Parisian life, not fanciful mythological subjects. They were the first artists to reject working exclusively in the studio, preferring instead to work extensively outside, in the fields, forest, streets, bars, and other sites of spectacle in and around France. They were not interested in making grand history paintings, rather they wanted a clean break with the Renaissance tradition. Artists since the 1500s had used every bit of their skill to convince viewers that flat canvases covered in paint were, in fact, portals into the real, three-dimensional world. They used perspective, foreshortening, three-dimensional forms modeled from dark to light, and many other artistic tricks to portray the Madonna and saints, rivers and streams, trees and mountains, and much more. This was art painted to replicate the way the mind understood reality.

The Impressionists, on the other hand, attempted to paint the way the eye saw things in the moment. They did away with many of the contrivances of the grand painting style that dominated Europe for four centuries. Compared to older artists, the work of the Impressionists seemed unfinished, a mere impression. Indeed, the term “impression” was at first hurled as an insult. In time it came to be the chosen name of one of the greatest art movements in history.

In the spirit of Monet, Hanson captures the outdoors, re-creating not just a picture but an experience or a story. In Waterlilies (2016), inspired by the water lily pond at the Norton Simon Museum, Hanson pays tribute to Monet. Here, she captured the beautiful late afternoon light of California, reflected in a tree-sheltered pool of water. Like Monet’s iconic treatment of the subject, Hanson delivers a scene that is more contemplative, more abstract, and less focused on narrative than her earlier scenes.

"Water Lilies" by Erin Hanson

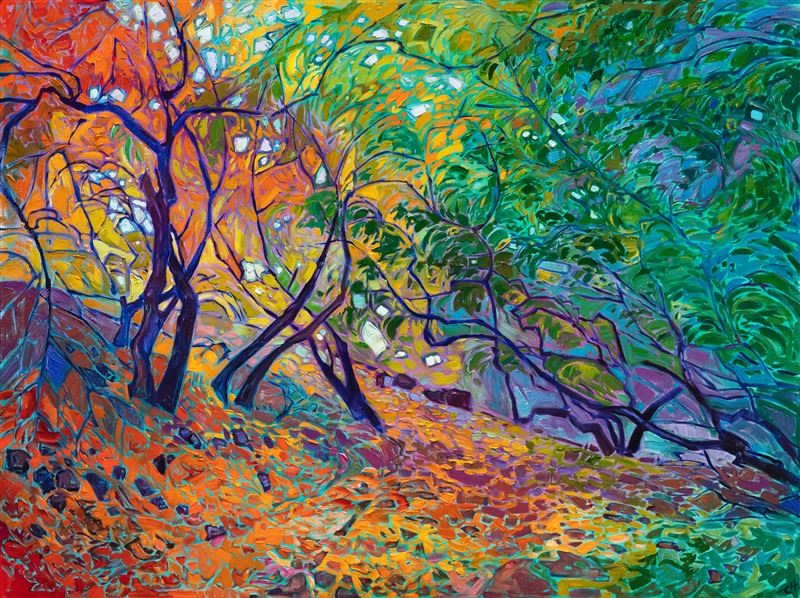

The generation that followed the Impressionists, the Post Impressionists, were a diverse group of artists who built on the Impressionist style. In Paul Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings, the artist pioneered the use of arbitrary colors; he used colors to express something other than how an object looked, allowing him to use colors symbolically rather than merely descriptively. Similarly, in The Path (2014), Hanson creates a vortex of sometimes arbitrary colors to suggest movement forward, literally but also suggests a symbolical, or even metaphoric, the path toward beauty.

"The Path" by Erin Hanson

In Vincent van Gogh’s masterpiece, Starry Night, the artist’s thick brush strokes record the troubled artist’s emotional state of mind rather than faithfully recording the scene outside his window. Brush strokes became a vehicle for emotions. In Zion Cottonwoods (2020), Hanson’s chaotic brushstrokes resolve into an immensely satisfying composition of movement and stasis. She suggests this almost entirely by her use of warm and cool colors. For Hanson, like van Gogh, “each painting is more of an emotional work than a photographic representation.” Like van Gogh and other Post-Impressionist, Hanson uses her bold, tectonic brush strokes to imbue her paintings with emotional content – joy, wonder, awe – for the viewer to revel in. Like Gaugin and van Gogh, Hanson uses color and brushwork to suggest the emotional impact of the scene. In this and other ways, she is heir to the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist mantle. Her paintings, built up as they are through vibrant, pure colors, are experiential and captured initially outdoors. Her subjects, especially the great American West, seem perfectly fit this modern, vibrant style.

"Zion Cottonwoods" by Erin Hanson

Perhaps most important, Hanson does not shy away from her place in history. When I asked her what contributions she hopes to make in the history of art, she replied:

"I have inspired thousands of artists to actually make a living as an artist. I believe there are many hundreds of would-be famous artists who would have brought more beauty to our world, but instead, they took a career as a doctor/lawyer/etc. (I speak from experience, having started as pre-med and taken a degree in bioengineering.) Imagine if more of our most brilliant and ambitious minds decided to take a career in art, how that would affect our society. So, by demonstrating to other artists that you CAN make a living as an artist, and a good living too, I have personally inspired many, many people to take up that brush.

"I also want to raise the emotional tone level of society through aesthetics and beauty. I can’t tell you how many emails I have gotten over the years telling me how my paintings got them through a rough emotional time, and how they actually are emotionally lifted every time they see my paintings."

To inspire others, to make art attainable, and to make the world better through beauty – these are the lofty but eminently attainable goals for one of America’s preeminent landscape artists. In time, Erin Hanson’s name may well be written in stone among other great American Impressionists from times gone by - Frank Benson, Mary Cassatt, William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Theodore Robinson, John Henry Twachtman, and William Wendt. In time, too, she may have a string of names attached to hers, other talented artists who learned the style and took it with them in their travels around the globe. In the present moment, I invite you to look closely at Erin Hanson’s paintings. I’m sure, like me, you will be richly rewarded for your efforts.

Discover the artist at the forefront of modern impressionism.

About Erin

ERIN HANSON has been painting in oils since she was 8 years old. As a teenager, she apprenticed at a mural studio where she worked on 40-foot-long paintings while selling art commissions on the side. After being told it was too hard to make a living as an artist, she got her degree in Bioengineering from UC Berkeley. Afterward, Erin became a rock climber at Red Rock Canyon, Nevada. Inspired by the colorful scenery she was climbing, she decided to return to her love of painting and create one new painting every week.

She has stuck to that decision, becoming one of the most prolific artists in history, with over 3,000 oil paintings sold to eager collectors. Erin Hanson’s style is known as "Open Impressionism" and is taught in art schools worldwide. With millions of followers, Hanson has become an iconic, driving force in the rebirth of impressionism, inspiring thousands of other artists to pick up the brush.