Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

Shopping Cart

Subtotal

$0

U.S. Shipping

FREE

Saved for Later

Louis Leroy was outraged. And the popular Parisian playwright, who also dabbled at painting and printmaking, was determined to expose an upstart group of artists—who had banded together to show their works in a new exhibition—for what he thought they really were: imposters.

Unlike the little boy of legend who dared to speak up in the public square and declare that the emperor was strutting about naked, Leroy confined his comments to print in a review he wrote for the April 25, 1874 issue of the satirical magazine Le Charivari. In the headline, he coined a mocking new term: “The Exhibition of the Impressionists,” taking that sobriquet in turn from the title of one of the paintings in the show: Impression: soleil levant (Impression: sunrise), by 33-year-old Claude Monet. Leroy’s description of the painting’s execution dripped with sarcasm: Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it… and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.

Louis Leroy, known as the man who

Louis Leroy, known as the man who

coined the term "Impressionism"

Rather than taking offense at such dismissive words, Monet and his cohort of artists in the show—including other rising but yet-to-be-heralded names like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and Alfred Sisley—wore the term proudly. The Impressionists, as they came to call themselves, gained still more members, including the American painter Mary Cassatt, and went on to hold eight more group shows over the next twelve years, with well-attended exhibitions outside of France including London, Boston, and New York.

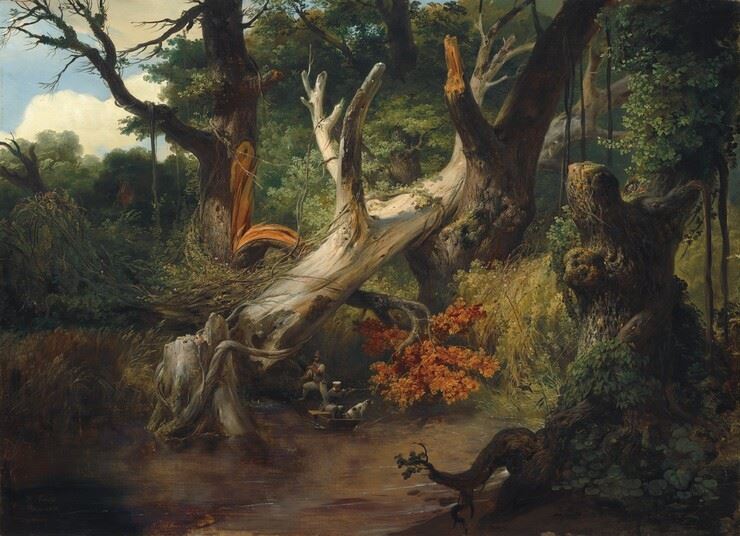

Members of the art-loving public saw in Impressionism what Leroy failed to appreciate. These were paintings that felt a world apart from studio works done in the then-prevailing Classical style, which were static and stodgy by comparison, or with the excessive idealization of the natural world so evident in Romantic Realism.

Horace Vernet, 1833, Paris

Horace Vernet, 1833, Paris

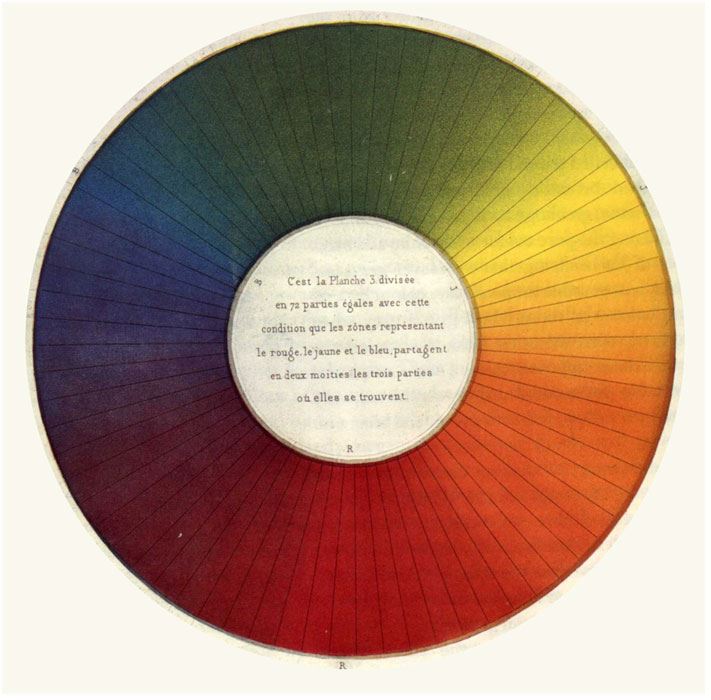

By contrast, Impressionism possessed a freshness and immediacy that resulted from executing the paintings at least partially en plein air, in the open air right on the scene, deftly combining loose brushstrokes with innate talent and solid studio training. In addition, Impressionists gained fresh approaches to color inspired in part by the theories developed earlier in the century by chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul, who observed the ways in which certain tones could be heightened by the close proximity of others: “The greater the difference between the colors, the more they mutually beautify each other.” A movement had been born that for many people came to define the best of fine art.

Michel-Eugène Chevreul's Color Wheel

Michel-Eugène Chevreul's Color Wheel

Daring to Be Different

Impressionists have often bravely taken the risk that their art and the intentions behind it might be misunderstood at first. Such daring is evident from those first officially “Impressionist” works by Claude Monet and his fellow artists to the emergence of California’s own version of Impressionism in the early 20th century, and then from a revival of the genre in the late-20th century to the rise of present-day painters working in their own dynamic reinterpretations—like Erin Hanson, with her often large-scale works created in a vibrantly energetic style that has become known as “Open Impressionism.”

"The Water Lily Pond", Claude Monet, 1904.

"The Water Lily Pond", Claude Monet, 1904.

Image courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

Yet, these aesthetic outliers all bravely persevered. Their efforts eventually were discovered and valued by art lovers who not only understood what they were doing but also ultimately came to appreciate their creations with finely discerning passion.

To gain such an aesthetic understanding, gallery and museum patrons who had been raised on works that aimed to faithfully reproduce the scenes they portrayed had to literally retrain their eyes. As the revered British art historian Sir Ernst Gombrich remarked in his book The Story of Art (1950), with reference to the dazzling array of rapidly executed brushstrokes necessary to capture a scene’s fleeting light in a plein-air scene: It took some time before the public learned that to appreciate an Impressionist painting one has to step back a few yards, and enjoy the miracle of seeing these puzzling patches suddenly fall into one place and come to life before your eyes. To achieve this miracle, and to transfer the actual visual experience of the painter to the beholder, was the true aim of the Impressionists.

The feeling of a new freedom and a new power which these artists had must have been truly exhilarating; it must have compensated them for much of the derision and hostility they encountered.

Needless to say, the avid sales and widespread adulation they ultimately enjoyed were no doubt exhilarating as well.

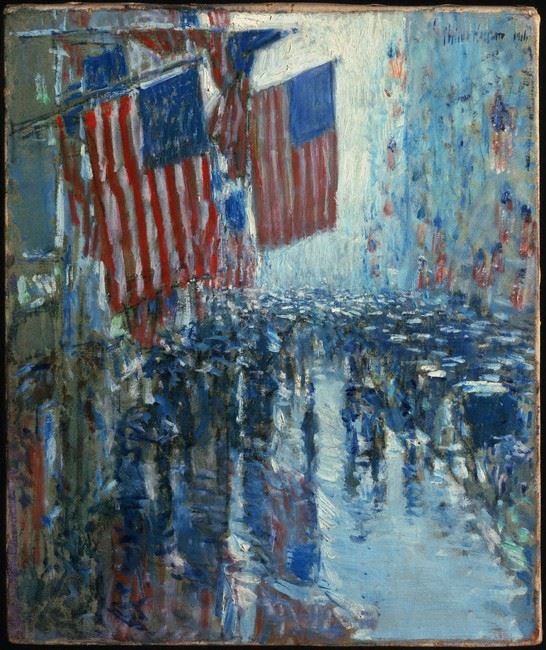

Under American Skies

Impressionism soon took hold among American artists who not only saw Impressionist shows in Boston and New York but also traveled and studied in France. Just a decade after French Impressionists exhibited their work on U.S. soil, the first show dedicated to the works of American Impressionists debuted in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair. Five years after that, the first organized group of American Impressionists formed in the northeastern United States, calling themselves “Ten American Painters,” an association more familiarly referred to as “The Ten.” Among them were such enduring names as John Henry Twachtman, Frank W. Benson, Childe Hassam, and Thomas Wilmer Dewing.

"Rainy Day" by Childe Hassam, 1916 (Image Courtesy of Princeton University Museum)

"Rainy Day" by Childe Hassam, 1916 (Image Courtesy of Princeton University Museum)

These artists, like their French antecedents, aimed to see the world afresh through their paintings. Some among The Ten came the hard way to their belief in and dedication to Impressionism. J. Alden Weir, another member, originally felt distaste for the movement: “I never in my life saw more horrible things,” he had remarked in 1877 in a letter he wrote home to his parents upon encountering works by the French Impressionists as an art student in Paris. “They do not observe drawing nor form but give you an impression of what they call nature. It was worse than the Chamber of Horrors.” By 1880, however, Weir had clearly changed his tune, even buying two works by Édouard Manet with proceeds from the sales of his own paintings.

Impressionism Comes to California

Just as the beautiful scenery and clement weather of France inspired so many of the first Impressionists, the “Golden State” of California began to move Impressionist painters to settle there in the final years of the 19th century and the first decade and a half of the 20th. A group of painters began working in the open air in and around the San Francisco Bay Area. But, following the devastating 7.9-magnitude earthquake that struck San Francisco on April 18, 1906, many of these artists headed southward to the frequent sunny days and beautiful coastline stretching from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles and on to Laguna Beach and still further south to San Diego.

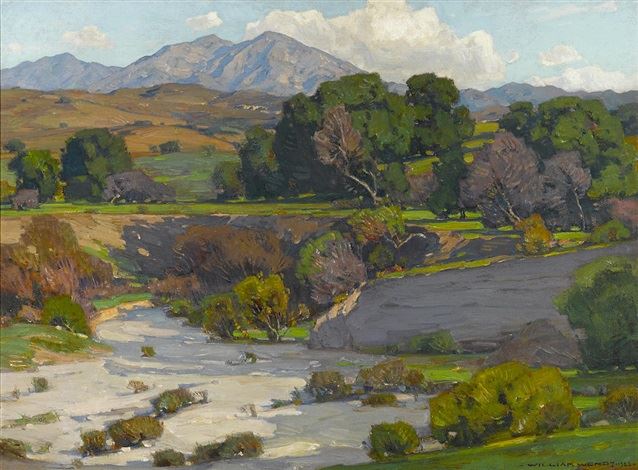

Luminaries of Southern California’s booming plein-air movement included Austrian-born Franz A. Bischoff, who settled in South Pasadena in 1906; German-born William Wendt, who moved to L.A. that same year and became part of Laguna Beach’s growing arts colony six years later; and landscape painter Edgar Payne, who in 1917 moved first to Glendale, near Los Angeles, and then to Laguna Beach. These and others including Elsie Palmer Payne (Edgar’s wife), William Lees Judson, Benjamin C. Brown, Donna Schuster, Granville Redmond, Guy Rose, and Franz A. Bischoff transformed this part of the state into “one of the most remarkable and distinctive schools of regional American art,” according to the scholar Jean Stern, Executive Director of The Irvine Museum, who is widely respected as the foremost expert on Southern California’s plein-air movement.

Working as they did more than thirty years later than those who first brought Impressionism to light, these New World practitioners possessed the perspective to wax even more philosophically about what was now a tradition in which they painted. “The average artist, if he chooses, could render an exact drawing of what he sees,” mused Edgar Payne, for example. “Artistic work not only allows but demands some deviation from form and line. Just how far this may go depends on the viewpoint of each painter.”

Plein-Air in Modern Times

Following the first heyday of California Impressionism, so much of the history of art in the 20th century seemed to turn further and further away from conventional representational art. That may not come as a surprise when viewed as a response to the turbulence of two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Atomic Age, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and other social upheavals. Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and numerous other “Isms”—not to mention Pop Art—seemed to suggest that mere pretty pictures were somehow no longer relevant or worthy of serious consideration. Some critics even derisively began referring to the California Impressionists of the early 20th century as “The Eucalyptus School,” so named for the scenic Australian trees that had been widely planted throughout California by the state government and appeared in so many regional plein-air landscapes.

And yet, this condemnation came more from the art historians and critics than as a true reflection of what mainstream art lovers were buying. Indeed, early Southern California Impressionists like William Wendt and Edgar Payne went on painting fine canvases that garnered general attention well into the middle of the 20th century, when critics and curators statewide began focusing anew on California Impressionism, an interest that only grew stronger through the end of that century and into the current one.

"Saddleback Mountains", William Wendt, 1923. Image courtesy of ArtNet.com.

"Saddleback Mountains", William Wendt, 1923. Image courtesy of ArtNet.com.

Meanwhile, new generations of Impressionists came onto the scene. The late Ray Strong, who passed away in 2006 at the age of 101, inspired and mentored plein-air painters in and around Santa Barbara, where he moved in 1960. In the 1990s, Pasadena-based artist Peter Adams, along with his gallerist wife Elaine Adams, revived the California Art Club, an association originally formed by Southern California’s first plein-air painters. Annual plein-air paint-outs and shows including major gatherings in scenic locations like Laguna Beach and Santa Catalina Island have come to attract major attention and showcase top Impressionists not just from California but also across the nation.

A Modern Maverick of “Open Impressionism”

Beyond such organized events, there are also mavericks in today’s Impressionist world, artists who have forged their own unique paths while holding dear the precepts that inspired their forbears. Prominent among such talents today is Erin Hanson, who now makes her home in northern San Diego.

"Carmel Lone Pine", Erin Hanson, 2020.

"Carmel Lone Pine", Erin Hanson, 2020.

Like the earliest Impressionists, the Los Angeles-raised Hanson has long been captivated by color—at least since the age of 6, when she was crestfallen that the irises she had planted in the garden with her mother lacked the vibrant hues of Vincent Van Gogh’s “Irises.” Says Hanson, “I knew even then that art could be better than real life.”

Educated in bioengineering at UC Berkeley, from which she graduated in 2003, Hanson had long nurtured a love for art as well as for science, selling commissions and dog portraits when she was 10 years old and working in a mural studio since the age of 12, then teaching herself Japanese painting and comic-book illustration while pursuing her college degree. She picked up her brush anew a few years later when, soon after moving to Las Vegas to rock climb at Red Rock Canyon, she found an ideal landscape full of vivid colors to inspire her artistic juices.

"Irises in Vase", Erin Hanson, 2019.

"Irises in Vase", Erin Hanson, 2019.

Hanson committed to completing one painting a week, finding ample inspiration for that steady pace in the brilliantly rust-colored sheer rock faces, deep purple shadows, and brilliantly blue desert skies. Just as the first Impressionists had done more than 130 years before, she amplified such colors by juxtaposing them with contrasting and complementary tones in bold brushstrokes that captured the very energy of the landscape itself. Her only departure from tradition grew logically out of the fact that such grand landscapes seemed to call for oversized canvases that did not lend themselves to plein-air work. Instead, Hanson soaked in the landscape through early morning hikes and tactilely through her fingers while climbing, and she used a camera to capture the effects of light, which she would later use as loose reference material when painting in the studio. Her entire goal when painting was to recreate what it felt like to be out of doors and to be face-to-face with Mother Nature.

Soon, Erin Hanson’s explorations took her beyond her beginnings at Red Rock Canyon, and she devoted herself full-time to art that celebrated the expansiveness of the still-unspoiled great American West, from the stark desert beauty of Joshua Tree National Park to the lush vineyards of Northern California, from the rugged coastline of Carmel to the dramatic rock formations and verdant vales of Zion National Park. With over 2,000 original oil paintings completed so far in her 15-year career, she has already surpassed many of the past greats in terms of perseverance. She came to refer to her personal style with the term “Open Impressionism,” paying tribute not only to the artists of the past who have inspired her but also to the wide-open vistas of the landscapes that she paints. “The purpose of Open-Impressionism is to capture the true feeling of being outdoors, each painting more of an emotional work than a photographic representation,” says the artist. “And color is how I communicate that emotional moment.”

Sounds like an approach with which the Impressionists who came before her would fully agree.

by Norman Kolpas

Discover the artist at the forefront of modern impressionism.

About Erin

ERIN HANSON has been painting in oils since she was 8 years old. As a teenager, she apprenticed at a mural studio where she worked on 40-foot-long paintings while selling art commissions on the side. After being told it was too hard to make a living as an artist, she got her degree in Bioengineering from UC Berkeley. Afterward, Erin became a rock climber at Red Rock Canyon, Nevada. Inspired by the colorful scenery she was climbing, she decided to return to her love of painting and create one new painting every week.

She has stuck to that decision, becoming one of the most prolific artists in history, with over 3,000 oil paintings sold to eager collectors. Erin Hanson’s style is known as "Open Impressionism" and is taught in art schools worldwide. With millions of followers, Hanson has become an iconic, driving force in the rebirth of impressionism, inspiring thousands of other artists to pick up the brush.